The HPO Axis

First: A Quick Recap of our ovarian hormones

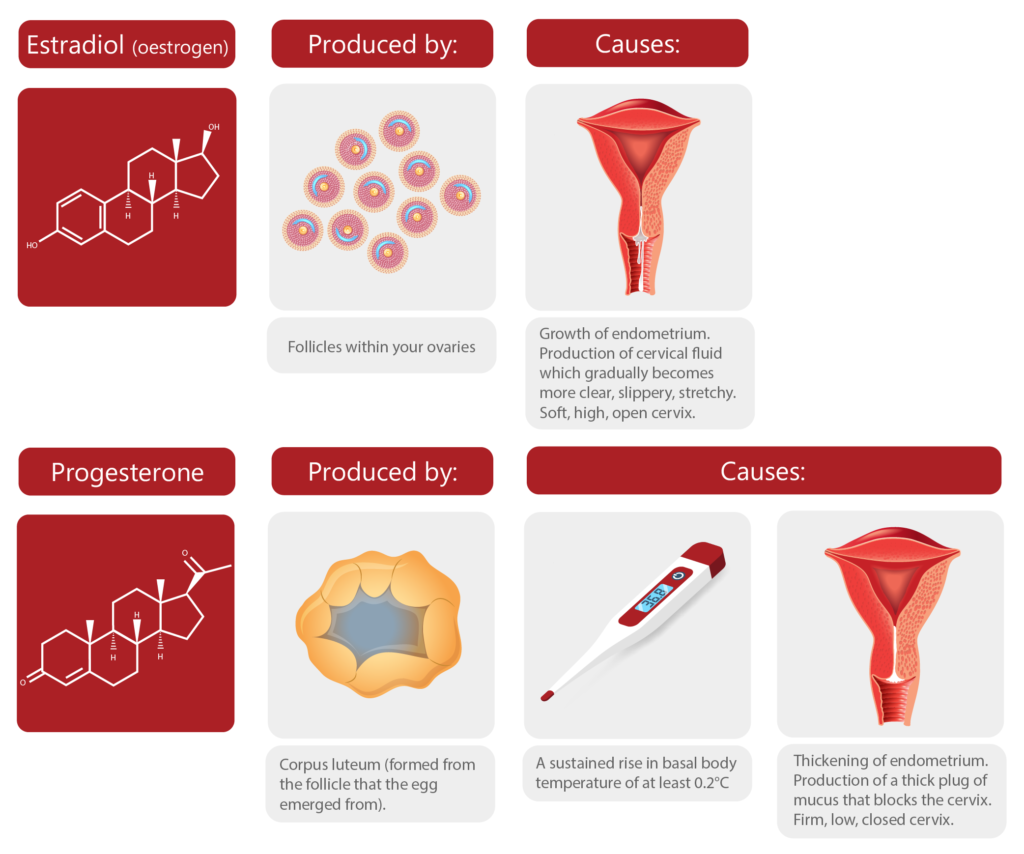

Our ovaries produce oestrogen and progesterone. These are our ovarian hormones.

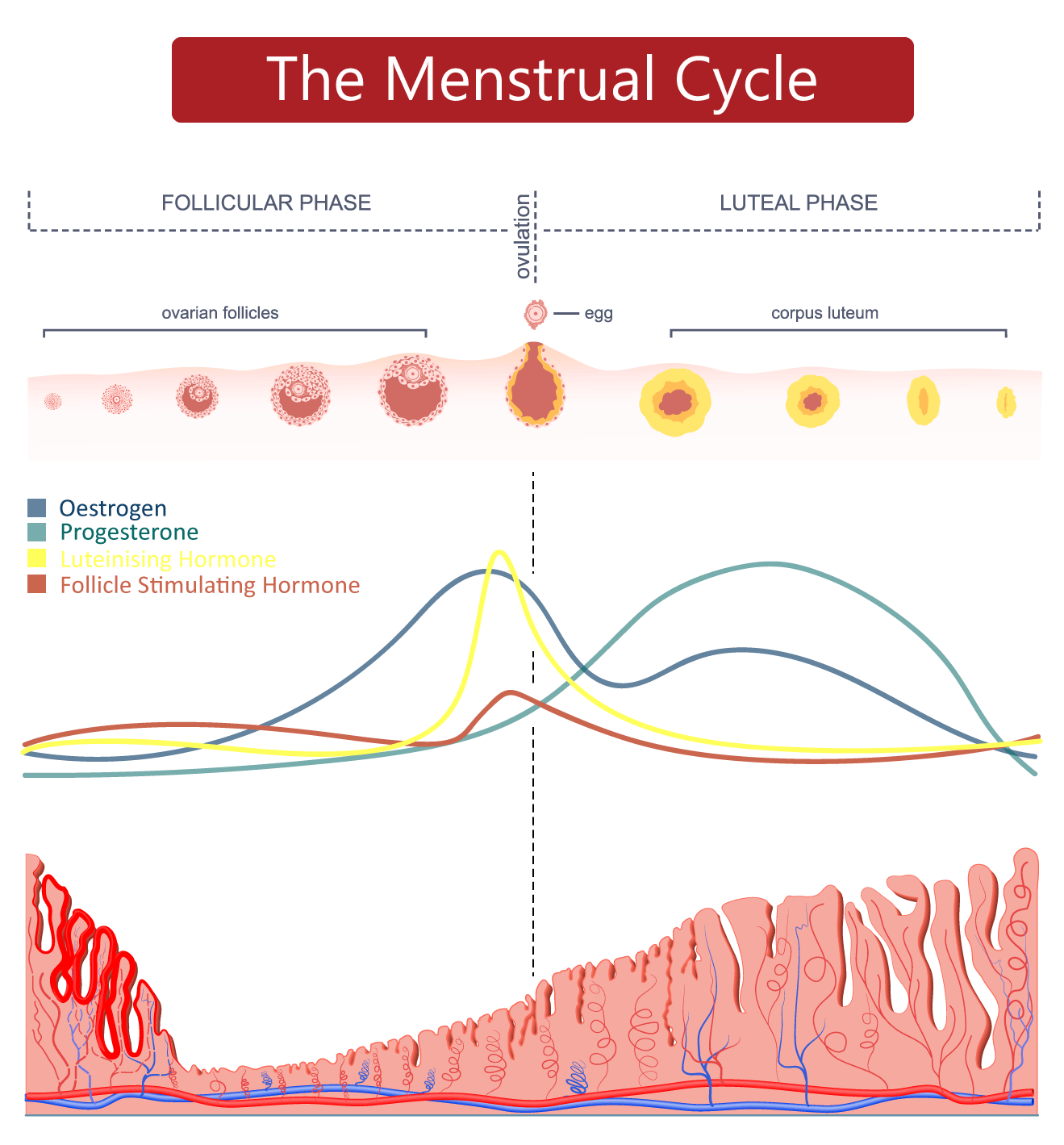

Oestrogen is produced by the follicles in our ovaries as they grow larger in the lead-up to ovulation. Our bodies produce 3 types of oestrogen – but estradiol is the type that is produced in our ovaries. When I refer to oestrogen throughout this course, I’m referring to estradiol.

Progesterone is produced by the corpus luteum (which is the temporary endocrine structure that forms from the follicle that the egg emerged from at ovulation). The corpus luteum also produces moderate levels of oestrogen.

Oestrogen causes the lining of the uterus to grow. It also affects the cervix and the mucus that the cervix produces. Oestrogen is also responsible for breast development and our female secondary sex characteristics.

Progesterone causes the lining of the uterus to thicken in preparation for a potential pregnancy. It also causes our core body temperature to rise. Progesterone is known as the “pregnancy hormone” because it primes the body for a potential pregnancy. In simple terms, the word progesterone is derived from the term “pro-gestation”.

But what causes our follicles to start growing larger and making oestrogen in the first place? And what triggers the egg to burst out of one of these follicles so that the corpus luteum can form?

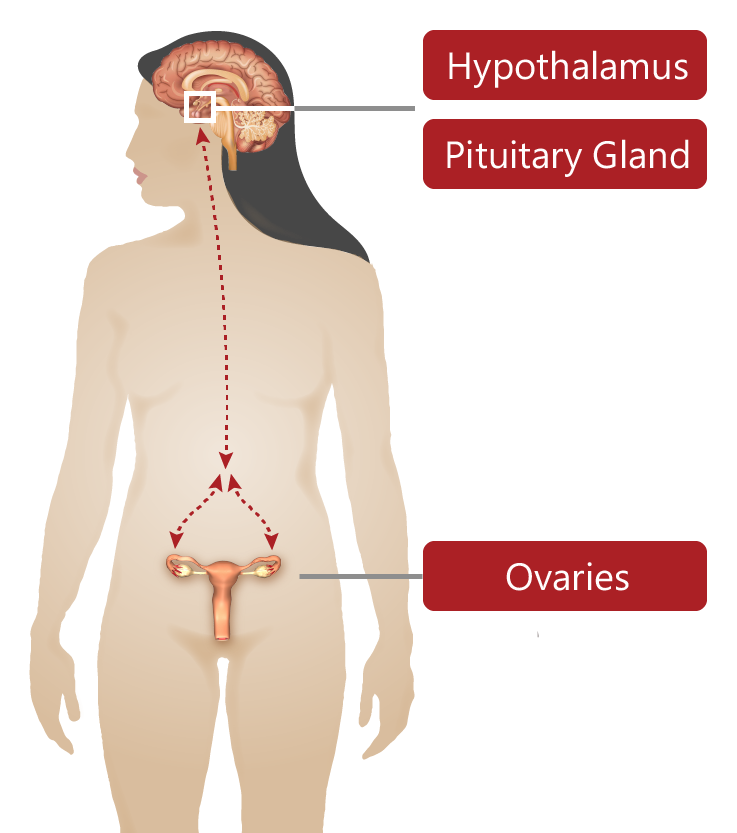

Welcome to the HPO axis – it turns out, your BRAIN is the CONTROL CENTRE of the menstrual cycle!

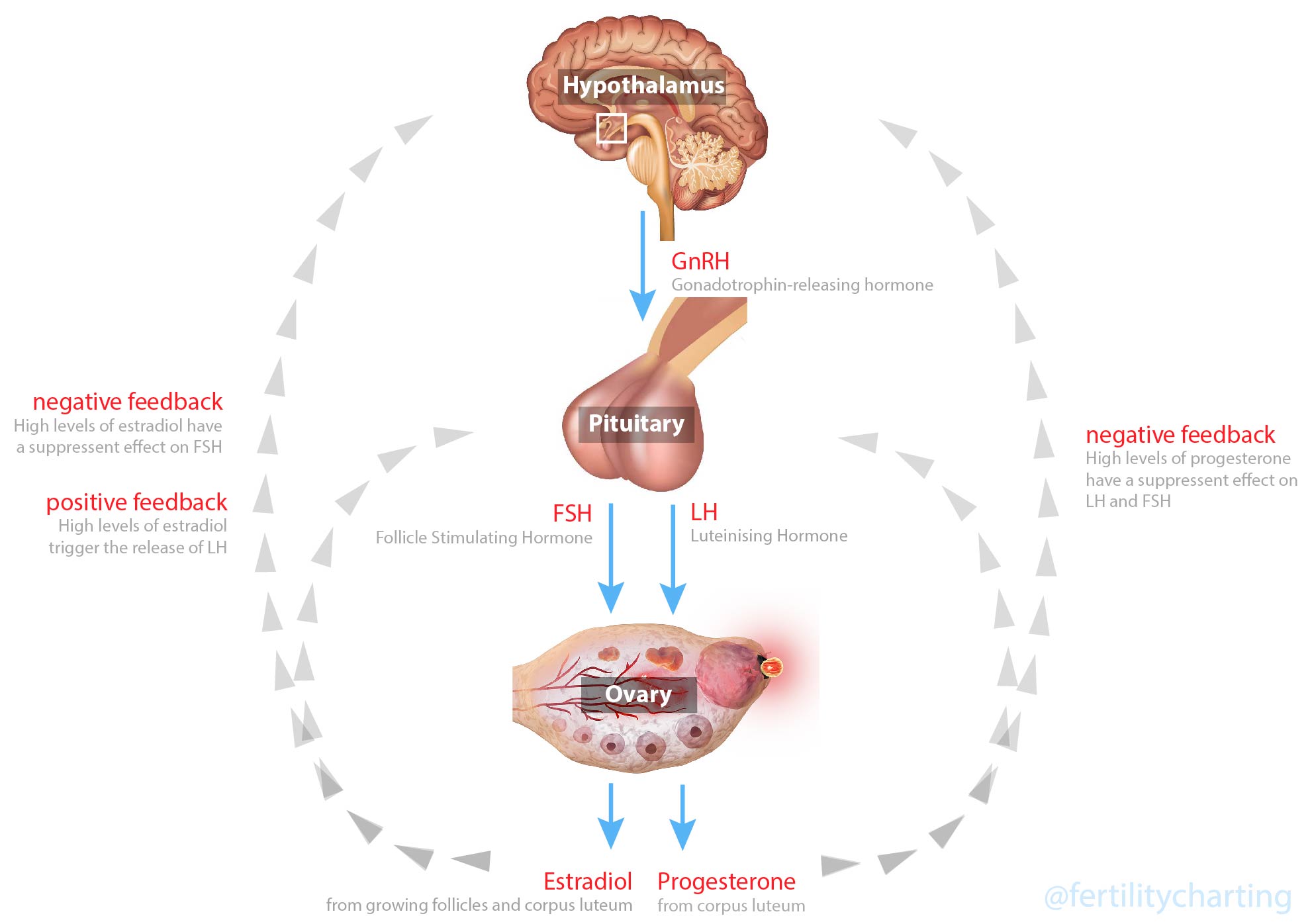

HPO stands for Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Ovarian axis.

Your HPO axis is made up of three different body parts:

- Hypothalamus

- Pituitary Gland

- Ovaries

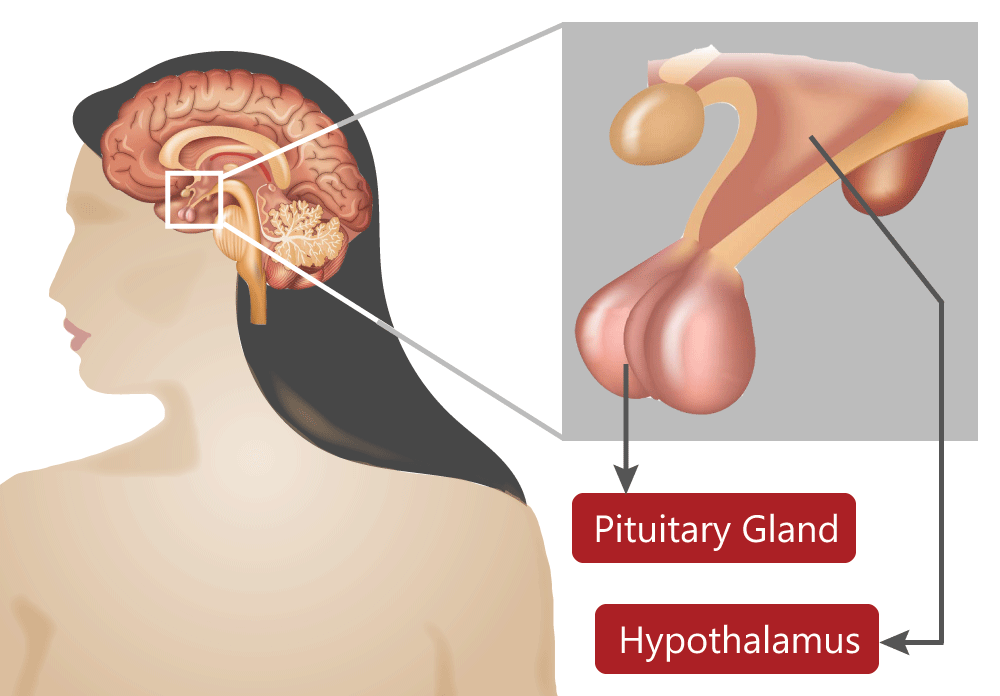

The hypothalamus is a small region in the centre of your brain. It is tasked with keeping your body in a state of balance. It does this by sending out hormonal messages into the bloodstream via the pituitary gland.

The pituitary gland is a pea-sized gland that is connected to the hypothalamus by a stalk. The pituitary gland creates different hormones for all different parts of the body. The hypothalamus sends different types of “releasing hormones” to the pituitary gland, telling the pituitary gland to release different types of hormones depending on what is needed in the body.

The hypothalamus and the pituitary gland are connected to our ovaries through a complex feedback loop of hormones. These hormones are in a constant dance – a small change in the level of one hormone, will create a counter-change in the level of another hormone. In this way, our HPO axis is the conductor of a cascade of hormones each menstrual cycle.

The reproductive hormones that the pituitary releases (when told to by the hypothalamus) are called “pituitary hormones.” The pituitary hormones are:

- Follicle Stimulating Hormone (FSH), and

- Luteinising Hormone (LH)

The hypothalamus controls the release of FSH and LH by sending out regular pulses of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) to the pituitary gland. GnRH tells the pituitary to release FSH and LH.

Follicle Stimulating Hormone

Follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) stimulates a group of follicles to begin growing in our ovaries each menstrual cycle.

As these follicles grow larger, they produce more and more oestrogen.

Oestrogen has a negative feedback effect on FSH. When oestrogen levels are high enough, levels of FSH are suppressed.

luteinising Hormone

When oestrogen reaches peak levels in your bloodstream, the hypothalamus is alerted. The hypothalamus signals the pituitary to produce a surge of luteinising hormone (LH).

LH triggers the first division of the egg inside the dominant follicle. LH also triggers the egg to burst out of the follicle. Finally, LH also causes the cells of the follicle to transform into the temporary endocrine gland: the corpus luteum.

During the luteal phase, the corpus luteum produces high levels of progesterone and moderate levels of oestrogen. When high enough, progesterone and oestrogen have a negative feedback effect on the hypothalamus and pituitary. Oestrogen and progesterone stop any further pulses of LH or FSH. This means that it is not possible for a second ovulation to occur outside of the 24 hour window of ovulation.

Getting Started

At puberty, the HPO axis has to begin functioning for the first time ever! It takes some time for the hormonal messaging systems to regulate. This is why many teenagers experience irregular cycles and heavy bleeding during the first few years of puberty. In many cases, they just need some time (and diet/ lifestyle/ supplementation support) for their brain-ovary communication to stabilise.

While this may all seem a little confusing – you really only need to remember these three main points:

- FSH causes groups of follicles to grow in your ovaries

- LH surges just prior to ovulation and is what triggers ovulation

- After ovulation, oestrogen and progesterone suppress FSH + LH. This means the 24-hour event of ovulation can only occur once each menstrual cycle (although multiple eggs can be released during this 24 hours).

One last important thing to note is that a surge of luteinising hormone (LH) doesn’t guarantee that ovulation will occur. It just means that your body is going to try to ovulate. There’s always a chance that the ovulation attempt will not be successful. However, if ovulation does occur it normally happens within 24 – 36 hours of the LH surge. We will discuss timing of ovulation in relation to the LH surge in more detail during Week 5.